x

Archive of the ‘discoveries of the month’ from the project

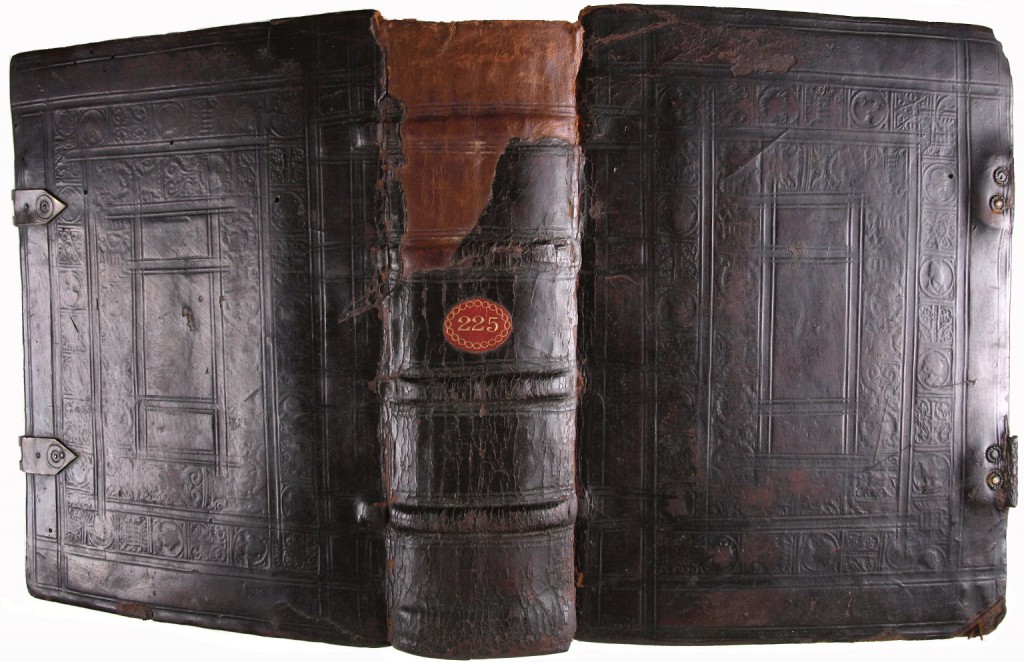

June 2025. In the first great age of print, books could be fatally absorbing. On 13 May 1553, at Maisemore in Gloucestershire, John Carpynter junior was deep in a book. Unfortunately, he was also too near an elm tree as William Elrundge was cutting off branches. One branch hit John on the right side of the head, and he died four days later. If anything, eight-year-old Susan Wigmore was even more inattentive. At Langley, Norfolk, on 6 March 1562, she came out of the house of Giles Fenne, gentleman, who was married to her aunt. She walked a few dozen yards to a fishpond or ‘stue’ with a book in her right hand. She was presumably concentrating too hard on the book as she fell – negligently, said the jurors – into the pond and drowned.

June 2025. In the first great age of print, books could be fatally absorbing. On 13 May 1553, at Maisemore in Gloucestershire, John Carpynter junior was deep in a book. Unfortunately, he was also too near an elm tree as William Elrundge was cutting off branches. One branch hit John on the right side of the head, and he died four days later. If anything, eight-year-old Susan Wigmore was even more inattentive. At Langley, Norfolk, on 6 March 1562, she came out of the house of Giles Fenne, gentleman, who was married to her aunt. She walked a few dozen yards to a fishpond or ‘stue’ with a book in her right hand. She was presumably concentrating too hard on the book as she fell – negligently, said the jurors – into the pond and drowned.

We hope our book, published this month as An Accidental History of Tudor England. From Daily Life to Sudden Death will be a fascinating read, though we trust it will not be dangerously so. Together with the book we are making available the spreadsheet of data on which it and our discoveries of the month have been based. We hope that readers of this column will enjoy as much as we have an exploration of the many and varied windows into Tudor life that accidents provide.

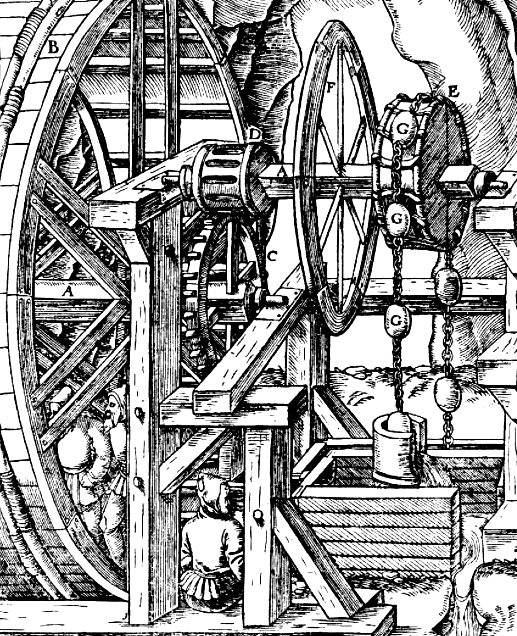

May 2025. Watermills were dangerous not only because of their fast-flowing millstreams and their fast-running machinery, but also because of the landscape engineering necessary to channel water to their wheels. At Stoke Mill in Bletsoe, Bedfordshire, at 8 in the morning on 18 May 1579, repairs brought calamity. Silvester Goore, a labourer from neighbouring Sharnbrook, and Mary Wright, a spinster from Radwell in Felmersham, the next village up the River Great Ouse, were working together. They were on the ‘bakewater’ next to the ‘milldamme’, in a boat belonging to the miller, Thomas Walton. It was loaded with ‘ramming claye’ to mend the breach through which the water flowed from the river towards the mill. The water was running so strongly that it burst out through the breach and swamped the boat. Both were drowned.

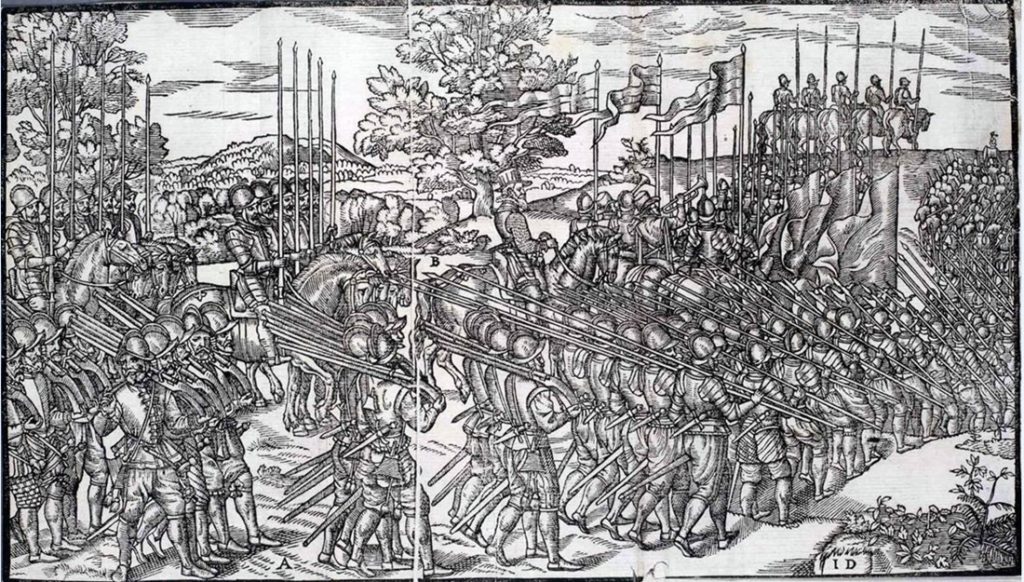

April 2025. Cattle were valuable in Tudor England, so it was important to keep them healthy. William Couper, a husbandman of Glatton, Huntingdonshire, had an ox with the barbs, an inflammation of the membrane under its tongue. On 16 April 1530, at 4 in the afternoon, he took remedial action with the help of his farming neighbours. Oliver Johnson held the ox by the head and Alice Leverche, wife of John, was standing by as William approached with a pair of tongs. He planned to cut out the inflamed flesh, as cattle care handbooks advised. The ox declined treatment. It knocked William to the floor so that he dropped the tongs and then gave Oliver a wound under his left arm from which he died three weeks later.

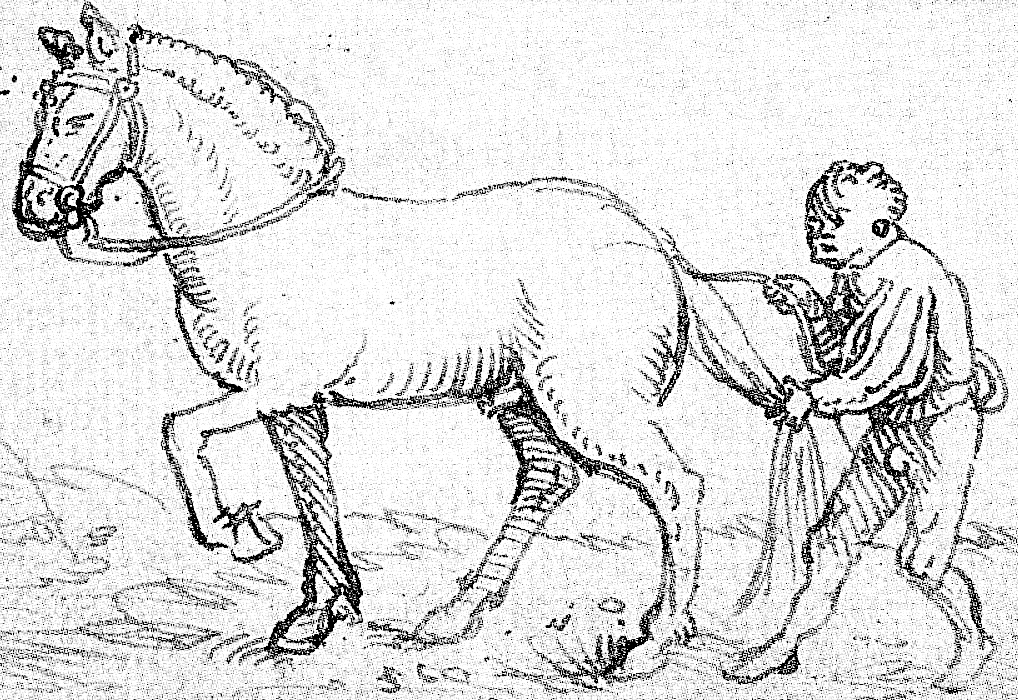

March 2025. The small-scale trade that tied together households all over sixteenth-century England can be hard to reconstruct. Mostly it went in and out of market towns, its agents might be men, women or young household servants, and its commodities were miscellaneous and dependent on the priorities of the local economy. James Nubee was 14 when he set out to ride from Bury St Edmunds to Lavenham on the evening of 20 March 1555. He was a servant of Roger Tryppe, probably one of the prosperous Tryppe family of Lavenham cloth entrepreneurs, and he was riding his mater’s gelding. On the horse he carried four cheeses, presumably bought in Bury, and a large bundle of woollen yarn, 40 lb (18 kilos) of it, presumably to supply Roger’s weaving business. By 8 p.m. he had reached Cockfield, two-thirds of the way home, but the light must have been fading. The horse stumbled into a hole and James fell under horse and load and was crushed. It is testimony to the economic weight of England’s cloth industry that when the various items involved were valued for forfeiture, the horse was worth 13s 4d but the three-stone bundle of yarn was worth 20s.

Bone dice recovered from Henry VIII’s ship the Mary Rose, which sunk in July 1545.

February 2025. Gambling disputes – often, no doubt, over accusations of cheating – produced knife fights in Tudor England just as they produced shoot-outs in the Wild West. Late in the evening, between 9 and 10, on 23 February 1556, the game was on in Bedford, at the northern end of the great bridge over the Ouse. Six craftsmen and tradesmen were playing dice, among them an innkeeper, a glover, a shoemaker and a tiler. John Clapham argued with Thomas Philips, the tiler, and snatched off his woollen hat. Philips fought to get it back and Clapham drew his dagger, more substantial and more expensive than an ordinary eating knife. In stabbing at Philips, Clapham cut his own left leg below the knee. Was his lack of coordination due to drink? The wound, two and a half inches long, a quarter of an inch wide and half an inch deep, must have gone through significant blood vessels, for inside two hours John Clapham had bled to death.

January 2025. Most buildings in Tudor England were timber-framed. One advantage of this construction system was that elements could be prefabricated and then joined to standing buildings. We can glimpse the process in action at Greet, then in Worcestershire, on 2 January 1553. John Byssyll was extending the ‘kytchyn’ of his house. Having assembled the new structure, he was moving it into place on ‘rollers’, working with Roger Carpenter, John Byddell, Richard Botter, Richard Pretty and others. As they dragged the frame, a piece of timber fell off it and landed on Richard Pretty’s head and body. It was probably a minor element – it was worth 4d when the whole new frame was worth forty times that – but it was big enough to kill him instantly.

The timber-framed cottage of Anne Hathaway, Shakespeare’s wife, Stratford-upon-Avon.

December 2024. Keeping livestock fed through the winter months demanded hay and lots of it, safely stored and regularly retrieved. In his house at Middlezoy in the Somerset Levels, John West had a ‘haitellet’ or hay-loft. On 11 December 1584 he was climbing into it to get hay for his animals, using not a ladder but a propped-up ‘herdelgate’ of wattle. His feet slipped and he slid down the gate, one of its stakes running into his belly six inches deep and two inches wide. Two days later he was dead from his wounds and the offending gate, worth 3d, had been taken into custody by his neighbours.

Thrashing grain in a barn. Illumination from ‘Hours of Henry VIII’ (c. 1500), The Morgan Library & Museum, MS H.8, fol. 4r.

November 2024. Thomas Tusser’s agricultural handbook Five Hundreth Points of Good Husbandry recommended November as a prime month for threshing the grain collected in the summer’s harvest. He warned of the danger that a reckless thresher might hit a cow when swinging the flail, two sticks connected by a leather joint, to beat the seed out of the straw and chaff. But even he did not reckon on the lack of coordination shown by Richard Rogers. Rogers was a servant of John Banester, a yeoman farmer of Hazleton, Gloucestershire. On 22 November 1573 he was threshing grain with another of Banester’s servants, John Jobborne. Somehow he hit himself in the head with the flail, giving himself a wound under his right ear, and three days later he was dead.

October 2024. Salt was indispensable for preserving and flavouring food but can be hard to track through the economy. It was extracted at saline springs like those of Droitwich and Nantwich and in coastal salt-pans; it was imported as ‘bay salt’ from south-west France; but it had to be distributed all over England, and for such a bulky load water transport was preferable. On 24 October 1576, William Milburye duly found himself among the crew of a boat loaded with salt. They were travelling on what the jurors called the Bridgwater River, the Parrett, a major artery leading from the Bristol Channel into the heart of Somerset. The salt was heading inland from Combwich towards Bridgwater, though whether it had originally come to Combwich down the Severn from Worcestershire or up the Bristol Channel from France we do not know. At 5 in the morning, between Cannington Pill, the stream flowing into the Parrett from Cannington, and Down End, a village by the East bank of the river, a storm hit the boat. It was swamped and William drowned, but his crew-mates presumably got away to tell the tale.

September 2024. The different landscapes of Tudor England offered different ways of making a living. Many of our coastal marshes have now been drained, but then much of the East coast was fringed with saltmarsh. It could be treacherous underfoot and it flooded fast, but it provided good grazing for sheep and cattle and distinctive vegetation. Reeds and rushes could be platted into mats for flooring, soaked in tallow to make rushlight candles or burnt under ships to soften the pitch with which they were caulked. Gathering them was a good way to supplement household income. On the afternoon of 15 September 1573 Rachel Kinge, 20-year-old-daughter of Thomas Kinge, was cutting rushes in Horsham Marsh at Upchurch in Kent, near the meeting-point of Medway and Thames. Surprised by the speed of the rising tide, she tried to make her way onto a bank. On the way she fell into a ditch, where her father found her drowned.

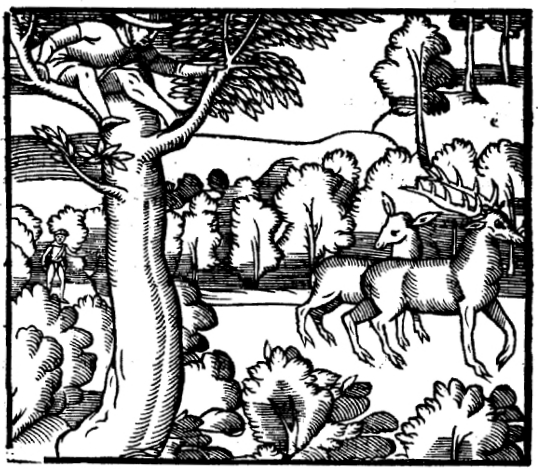

August 2024. Some accidents shed a sudden shaft of light on a situation but leave many questions unanswered. On 12 August 1532 a cart drawn by five horses overturned at Campsall in Yorkshire, some 8 miles north of Doncaster, perhaps on or near the Great North Road. It was carrying seven of King Henry VIII’s hunting hounds, fine animals together worth a total of £4, the cost of a high-quality horse. The driver, killed in the crash, was a labourer based at Woking in Surrey, a royal house often visited by the king on his hunting tours, and after the crash the hounds were taken into custody by Robert Shere, also of Woking.

Royal kennels. Woodcut in George Gascoigne, The noble arte of venerie or hunting (1575), title page.

These two men take us deeper into the court of the 1530s. The driver was called Urian Trigg, sharing an unusual name with the Cheshire courtier Urian Brereton. Had some Cheshire connection been his route into royal service? Robert Shere was a servant of Francis Weston, lately the king’s page and now a gentleman of his privy chamber. Was Weston, who gambled and played tennis at court, also involved in the royal hunting establishment? If so, his role would end in 1536 when he lost his life as one of the alleged lovers of Queen Anne Boleyn, together with Urian Brereton’s brother William. And the hounds were nowhere near the king, who was in Oxfordshire. Were they perhaps on their way as a gift to his nephew the king of Scots – the two countries were teetering on the edge of war – or to one of the northern nobles whom Henry would need to mind the border while he travelled to Calais that autumn to meet King Francis I of France?

July 2024. Pranks can enliven the dullest working day, but occasionally they misfire. At 10 in the morning on 15 July 1549, at Rowde in Wiltshire, William Byrde was shoeing a horse. His neighbour Walter Barnarde – they were both small farmers in the village – decided to have a joke with him. As William was busy with the horse, holding its foot in his hand, Walter threw some dust down the back of his neck. William instantly kicked dust back at Walter. Unintentionally he kicked with it a tool lying behind him, a blacksmith’s buttress used to trim horses’ hooves. The buttress hit Walter on a vein in his leg, near the heel, and began an unstoppable flow of blood. Seven hours later, jesting Walter was dead.

June 2024. Working with animals always has an edge of unpredictability, especially when animals interact. At Hastingleigh in Kent on 18 June 1583, Thomas Everenden was driving a dung cart between the house of his master, Christopher Bellyng, yeoman, and the fields. As the cart was empty, he was riding on it. The draught team of two oxen and a mare suddenly pulled the cart off in the wrong direction and Thomas leapt out to avoid a crash, only for the left wheel to run over his head and kill him instantly. The cause of the animals’ panic, explained the jurors, was a maddening attack by biting flies, or ‘bremps’.

May 2024. Play can get rough, especially between boys. At Over Whitacre in Warwickshire on 18 May 1598, 11-year-old Anthony Dyvett was playing, or so the jurors chose to describe it, with 7-year-old Edward Lunkeslow, hitting him with his ‘leather Sachell’, perhaps a school bag. The satchel contained an unsheathed knife which cut through the satchel and into Edward’s abdomen, 3 inches deep, and Edward died next day.

April 2024. Country walking after rain can be a muddy business, but in the sixteenth century mud could be lethal. On 13 April 1586, Peter Cowles set out to walk the three miles from Sandhurst to Gloucester, but wandered off the certain road, as the jurors put it, into a muddy lane called ‘Bearde lane in Sandhurst’. He fell into the earth and mud there and struggled to get out. Late in the evening he managed to scramble into a field on the north side of the lane called ‘Newclose’, but around 11 at night he died there from cold and exhaustion.

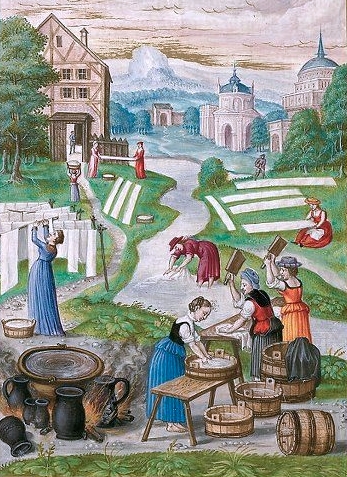

Women doing laundry. Illustration from Splendor Solis (1582), British Library, Harley 3469, fol. 32v. Click to enlarge.

March 2024. Laundry was one of the household tasks that exposed women regularly to the risk of drowning. Usually, it was a matter of a simple slip into a river or pond, but sometimes accidents were more complex. Alice Malyne, widow, was doing the washing at Earith, Huntingdonshire, on 19 March 1576. To make it easier to carry a very large linen sheet – the jurors reckoned it was about 11 feet long – she pinned it round her shoulders. As she walked between the ponds in the yard by her house, there was a sudden windstorm and the sheet got entangled round her head. Temporarily ‘blyndfelde’, as the jurors put it, she stumbled into one of the ponds and drowned.

February 2024. While concerted building throughout the middle ages had provided England with an impressive network of bridges, many rivers and streams were still best crossed by fords. They were used by pedestrians, riders and cart drivers, but in winter’s winds and floods they could be treacherous. On 21 February 1596, William Erigs met characteristic difficulties. He was taking the cart of his master, John Bayes of Tempsford, Bedfordshire, husbandman, across the Great Ouse at Tempsford Ford. He rode on the back of the front horse in the team of horses drawing the cart, presumably to keep his feet dry. It was 7 in the morning and it may not have been easy to judge the state of the river. The strong current dragged at the horse and its harness, turning them round and sweeping William into the water, where he drowned.

January 2024. Hawking was a more flexible form of hunting for the Tudor elite than the pursuit of deer. It could be practised alone, and hawks could take a variety of game, from rabbits to partridges. Thomas Samborne was fortunate to have a goshawk, an effective woodland hunter of which numbers had to be imported because the domestic population was too small to meet the demand for birds that could be trained. At Send in Surrey on 5 January 1516 he was trying to build a ‘perche’ for his bird by cutting down a small oak with his ‘Wodknyffe’, a substantial hunter’s tool. Halfway through the task, he threw the wood-knife aside. It landed on the ground point upwards. As he pulled the oak downwards, the rotten branch he was holding snapped and he fell. He landed on the wood-knife and wounded himself 20 inches deep, from his thigh through to his stomach, dying unsurprisingly fast.

The goshawk and a falconer. Woodcut illustrations from George Tuberville’s Book of Falconry or Hawking (1575), p. 58 and 75.

December 2023. Tudor courtship can be reconstructed from various angles, from letters, romantic literature and church court cases about who was really married and who was not. Fatal accidents rarely shed light on it, but when they do, the events they describe combined the mundane with the dramatic. At Holwell in Somerset on 14 December 1565, Jerome Snouke, a household servant, spotted Grace Wyseman, a young woman towards whom, as the jurors recorded, he felt an ardent desire of marriage. He ran fast towards her to give her a kiss. Grace was holding a willow rod in her right hand and, against her will, it poked him in the left eye. He died four days later from a wound to the eye one inch deep and one inch wide.

Grace Wyseman pursued by Jerome Snouke. One of the images from the freshly released Accidental Tudor Deaths TOP TRUMPS card game. Click to find out more!

November 2023. Accidents often show us the practical problems of working life, but glimpses of social life at work are rarer. At Staplehurst in the Weald of Kent on 30 November 1525, James Kyng and William Fermor were in a ‘Workhouse’ belonging to William Scranton. The Weald was a centre of the cloth industry and William was presumably an ancestor of the Thomas Scranton who was operating as a cloth-manufacturer at Staplehurst in the next generation. James and William were sitting by the fire eating bread, cheese and other food for breakfast. They were larking about and James playfully nudged, or perhaps barged, William with his shoulder. In his left hand, William held the knife for cutting his food and James’s nudge pushed it into James’s left thigh. It went in half an inch deep, presumably severing an artery, and James rapidly died.

October 2023. Ferry boats, sometimes called passage boats or passing boats, were necessary for crossing many rivers too deep to ford or too wide to bridge. One persistent cause of capsizes was the presence of restless animals. The jurors at Saint Dominick in Cornwall described one such mishap in vivid detail. On 18 October 1595, at about 8 in the morning, Richard Cornishe was in a ‘passing Bote’ on the River Tamar below Halton chapel, in the liberty of the town of Saltash. Also on board was an ox. The ox was restrained, ‘tyed by his hynder legges’, but resolved on ‘leapinge out of the said Bote’, such that ‘the rest of his bodie fallinge over the said Bote into the said River of Tamer’ caused the boat to sink and Richard drowned.

This horse leg bone is nearly 50 cm or 20 inches long – large and heavy enough to use for throwing in lieu of a hammer.

September 2023. As we have seen before, football was the great winter sport of Tudor England, throwing the hammer the great – or at least the most dangerous – summer sport. But what could one throw if there were no sledge-hammers to hand? At East Witton in Wensleydale on 1 September 1532, a group of young men and boys had an answer. They were playing on a Sunday afternoon at 5 pm, a classic time for sport, throwing the leg bone of a horse. Robert Asvyth, a labourer from the neighbouring village of Jervaulx with its great Cistercian abbey, let fly with his right hand. The bone hit Henry Pacok on the left side of the head and three days later Henry expired.

August 2023. August, at the height of harvest, was a prime time for loading and unloading carts. One key element was the cart rope with which loads were tied down. At Ilchester in Somerset on 25 August 1584, William Hodges, senior, was working with his servant Pancras Savage in a field called ‘Footes meade’, a name that survived into the nineteenth century. They were loading a cart with barley, and, as the jurors put it, tying a rope around the grain as is the habit of the countryside. They tied a knot in one end of the rope and fixed it to the cart. Then William stood on the ground and Pancras, presumably younger and more agile, on the cart. William threw the rope up onto the cart and they each pulled it tight. But as they pulled, the knot slipped off the cart and Pancras fell to the ground, breaking his neck and dying two days later. Similar accidents add other details – ropes that broke, others that came off the ‘cart pynn’ or ‘naile’ to which they were fastened, loaders who fell backwards head-first 8 feet from a cart or landed on a ‘a flynt stone’ such that their brains came out – that show just why securing cart loads was such a hazardous business.

July 2023. Sixteenth-century critics of monks – often of course spurred on by a desire to close their monasteries and confiscate their lands – might accuse them of any of the deadly sins. Gluttony, strictly warned against by monastic founders such as St Benedict, was a particularly frequent charge. We might wonder if the inquest jurors or others who heard of his fate levelled it at poor John Emere. He was a monk at Sawtry Abbey, a Cistercian house in Huntingdonshire. On 18 July 1528 he fell to an instant death, having climbed into the roof of the abbey church in search of pigeons. Perhaps, of course, the birds were not to enliven the fare at the refectory table, but to equip the abbey’s guest house, much frequented by travellers on the nearby Great North Road.

June 2023. Coroner’s inquest reports often report both the date and time of the victim’s death and the date and time of the incident that caused it. We can use this to work out how rapidly different kinds of injuries proved fatal. One horribly lingering category of deaths was that caused by burns and scalds. Only a quarter of those who died as a result of them expired more or less immediately, compared, for example, to nearly nine in ten of those with broken necks. One in five died later on the same day, a quarter on the following day, and three in ten lasted until two or more days later. The cause was often hot wort used in brewing ale or beer. On 19 June 1570, at Great Braxted in Essex, Clemency Coxe, servant of Brian Darcy esquire, was pouring water from a ‘cowle’ or tub into a brewing copper. Her feet slipped and she fell backwards into a mashing vat full of hot water. Her body was scalded all over except for her head and feet, but she did not die until eleven days later, at noon on 30 June.

May 2023. One of the many perilous tasks of Tudor agriculture was the spreading of marl on the fields. Marl, a mixture of clay and chalk, was added to light or sandy soils to improve their fertility, above all in the chalky counties, from Dorset and Hampshire through Berkshire and Hertfordshire to Bedfordshire and Norfolk, but also beyond. Early summer from May to July was the prime time for marling. It was rarely the spreading that was the problem, it was the excavation. Marl pits had an alarming tendency to cave in as they grew deeper or their sides more undercut. One collapse came on 27 May 1554, in a pit in the fields at Carr, near Rotherham in Yorkshire. Two labourers, William Ledebeter of Carr and William Warren of Slade Hooton, were digging with a husbandman, Roger Cosyn of Newhall. At 6 in the evening, the earth around the pit collapsed and killed all three.

April 2023. Many of the heavy industries of later centuries were expanding in sixteenth-century England, often inspired by foreign expertise. The first iron-slitting mill on this side of the Channel appears to have been set up by Godfrey Box, an entrepreneur from Liège, at Dartford in Kent in around 1590, processing iron from the growing Wealden smelting industry. On 3 April 1600 an inquest at Dartford heard how one of Box’s servants, Anthony Vahey, had met his end on 30 March. At 2 in the afternoon in the ‘myll fielde’, presumably by Box’s mill, Vahey had given a drink to Thomas Edwardes. Edwardes was a servant of Robert Kettell, a Dartford yeoman. He was driving a cart pulled by four geldings and loaded with various pieces of iron, heading form Dartford to Box’s ‘Iron myll howse’. Edwardes had too much of the drink and drunkenly hit one of the horses with a stick so hard that it left the road and pulled the cart up a hill in the field, overturning it. In the crash an iron bar hit Anthony in the head and two other pieces hit his left arm, killing him at once.

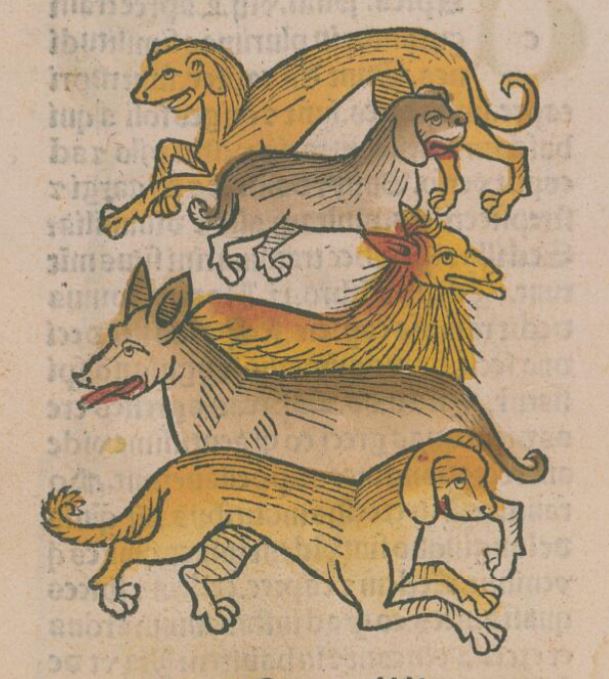

Different breeds of dogs. Illustration in Jacob Meydenbach, Hortus sanitatis (Mainz, 1491), Wellcome Collection, London, 5.e.12. Click to view the full page.

March 2023. Sixteenth-century guard dogs were meant to be fierce, but when they got out of control the results could be horrific. At 4 in the afternoon on Sunday 1 March 1562, Edmund Pryckett was at evening prayer with the members of his household in Bungay church, Suffolk. They had left behind one 16-year-old maidservant, Elizabeth Sprat, but she, it seems, was oblivious to the bloody drama unfolding in the yard by Edmund’s house. Edmund was a tanner. Stockpiled in the yard he had hides and tanner’s bark, the acidic oak bark used to tan the hides into leather. Perhaps knowing that the master and most of his servants were away, twelve-year-old Andrew Dedynham got into the yard, aiming to steal some of the bark. He had not reckoned with Edmund’s three guard dogs, who fastened on him, biting him in the head and under the arms. He died two days later.

February 2023. Excavations at the London theatres of Shakespeare’s day have shown how enthusiastically playgoers guzzled oysters and threw away the shells. They were kept supplied by the oyster fisheries of the Thames estuary. At Gillingham on 5 February 1566 the costs of the trade became clear. That morning Richard Wood took his two sons, Thomas and Edward, out in his small boat, a ‘dredging cock’, to dredge for the shellfish. They were on one of the salt creeks of the Medway marshes, Bartlett Creek, to the east of the town. By 11 they had filled the boat with oysters and were heading back towards the bank, but the wind got up. The boat filled with water and they all fell out. With the help of two other fishermen, Edward Geere and John Grygg – and, the jurors reverently added, by the favour of God – Richard and Edward made it to safety, but Thomas drowned.

Hare hunting with a crossbow and a bow. Detail from a miniature in Gaston Phébus’s Livre de la chasse (c. 1410), Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Français 616, fol. 118r. Click to enlarge.

January 2023. Rabbits were valued, indeed farmed, in Tudor times not only for their meat but also for their fur. They were a prime target for hunters and poachers. On 25 January 1515 at Musbury in Devon, John Frankecheyny and Richard Smith of Axminster thought they had one cornered in a hedge as they stood on either side of it. John encouraged Richard to shoot, but Richard’s arrow missed the rabbit, ricocheted off a branch of the hedge and hit John in the face, presumably at close range. Stunned, John fell into a ditch and suffered injuries from which he died six days later.

December 2022. It is rare for buildings in which sixteenth-century accidents occurred to have survived to the present day. One which has, at least in part, is the Bedern at York. The Bedern was the home of the succentor and vicars choral of the cathedral, who sang in York Minster’s services. It was in the kitchen attached to the hall that a young man, Oswald Gylfeld, a servant of the succentor and vicars, was at work at 11 in the morning on 17 December 1565. Part of a brick chimney in the kitchen – a fashionable and efficient but sometimes unstable aid to cooking – suddenly fell on him. He was instantly killed.

November 2022. Provision for the poor in Tudor England ranged from the traditional – individual charity to neighbours, endowed almshouses – through the innovative – parish poor rates and apprenticeship schemes – to the brutal, slavery for vagrants under a short-lived act of 1547. Workhouses, or bridewells as they were called after the former royal palace in London where the first was established, were at the more repressive end of the spectrum. There the apparently workshy or reprobate were confined and set to work. Mabel Ockford was presumably an inmate of the ‘Bridwell’ at Gloucester, which may already have been housed in the city’s East Gate, when she was at work there at 3 in the afternoon on 4 November 1589. She was driving the horse that powered a ‘mault mill’ to grind up barley for brewing when she fell between the beam of the mill and the wall of the building and was crushed to death.

Building a timber-framed house. Illustration in the ‘Hausbuch der Mendelschen Zwöflbrüderstiftung’ (1426-1549), Stadtbibliothek Nürnberg, Amb. 317.2°, fol. 76r. Click to enlarge.

October 2022. Construction in Tudor England was a professional job for carpenters and masons, but timber-framed buildings in particular were also suitable for DIY. William Turnor of Eastwood, Essex, yeoman, was repairing his house on 20 October 1586 when disaster struck. His wife, Mary, was helping him erect a timber beam by supporting it on a two-pronged pitchfork. The beam must have been quite substantial, as it was worth 2 shillings, several days’ wages for a labourer. It slipped off the fork, knocking her backwards to the ground and crushing her head, so that she died instantly.

September 2022. Walking to church and back could be a sociable time in Tudor England. At Kingsnorth in Kent on Sunday 22 September 1566, morning prayer had finished by 11 o’clock and William Cloke was heading home to the house of his master William Chalcroft. He was described as a labourer, so was probably a young live-in farmworker. He was presumably a local boy, for among the jurors who sat at his inquest were Michael Cloke, John Cloke senior, John Cloke junior and Robert Cloke. Among his companions was Michael Colbrand and they were larking about, or as the jurors put it, playing together in game and sport. William suddenly jumped onto Michael’s back and they both fell over. The knife hanging at William’s belt had a broken sheath and as he fell it poked through and went an inch and a half deep into his left thigh. It must have hit an artery as he died at once.

August 2022. Fields at harvest time were full not only of activity but of obstacles for the unwary. At 10 in the morning on 25 August 1585, John Padmore and his servant were driving his cart from a meadow called ‘the Snappe’ to the village of Cheswardine in Shropshire, carrying ‘a lode of haye’. The four oxen drawing the cart came down ‘Cheswardyn bank’ and straight through some sheaves of wheat left lying on the ground. John went to clear the wheat out of the way and pull out one sheaf that had caught under the cartwheel. As he tugged, the wheel fell on his leg and broke it. He made it home but died five days later, leaving the cart and the hay in the hands of his widow Joan.

A hay cart. Simon Bening’s illumination in the ‘Golf Book of Hours’ (c. 1530), The British Library, Add MS 24098, fol. 25r. Click to enlarge.

July 2022. The county gentry were key figures in Tudor society and government. They linked local communities to the centre through hospitality and office-holding, though some were resented for harsh landlordship. Thomas Guldeford esquire, of Hemsted House, Benenden, Kent, was an obscure member of a declining family; if indeed he existed at all, and was not a slip of the pen for Henry Guldeford esquire, the adolescent heir of the late Sir Thomas Guldeford. Yet he seems to have been popular, to judge from events on 10 July 1587. On that day he was returning home after a long absence. A crowd of his neighbours, led by Walter Everenden of Benenden, yeoman, and Richard Reve of Cranbrook, cutler, made surprise plans to celebrate his homecoming. In a joyful mood, they laid along the road to the house a line of gun chambers loaded with gunpowder and paper, together with a train of powder to set them all off in salute. Walter and Richard then left the scene for half an hour, during which time an unknown person set light to the train of powder. The chambers went off with a great noise and such force that pieces of broken iron and a splintered wooden peg flew about. Hugh Jull, a Benenden labourer, who was standing waiting to enjoy the spectacle, was hit. The iron lacerated the flesh, veins and bone of his right leg between knee and foot and two weeks later, at his home in Benenden, he died.

A gentleman giving alms to a beggar. Woodcut in Stephen Bateman, A christall glasse of Christian reformation : wherein the godly maye beholde the coloured abuses vsed in this our present tyme (1569), p. 63.

June 2022. Ploughmen and carters in different parts of England generally chose horses or oxen as draught animals depending on the heaviness of the local soil. Surprisingly often, however, they combined both. In June 1552, for example, John Bott of Bevington in Warwickshire, husbandman, and Robert Glaspole, far away in Hampshire, met their ends driving mixed teams. John was sitting on a cart laden with a quarter and a half of malt, drawn by six oxen and two horses, when he fell asleep on the road between Banbury and Hardwick. He fell from the cart and his servant Maurice Shawe shouted at the animals to stop them, but it was too late and the cart ran over a molehill and crushed John’s body. Robert was walking by his cart loaded with wood and pulled by two young oxen and four horses as it came down a hill on Colden Common. His feet slipped, he fell and was run over by the left wheel, breaking his back and wounding his kidneys. Injured at 11 in the morning, he died at 4 in the afternoon. Whether there were advantages in mixing animals in this way, or whether people just assembled whatever teams they could, is an interesting question.

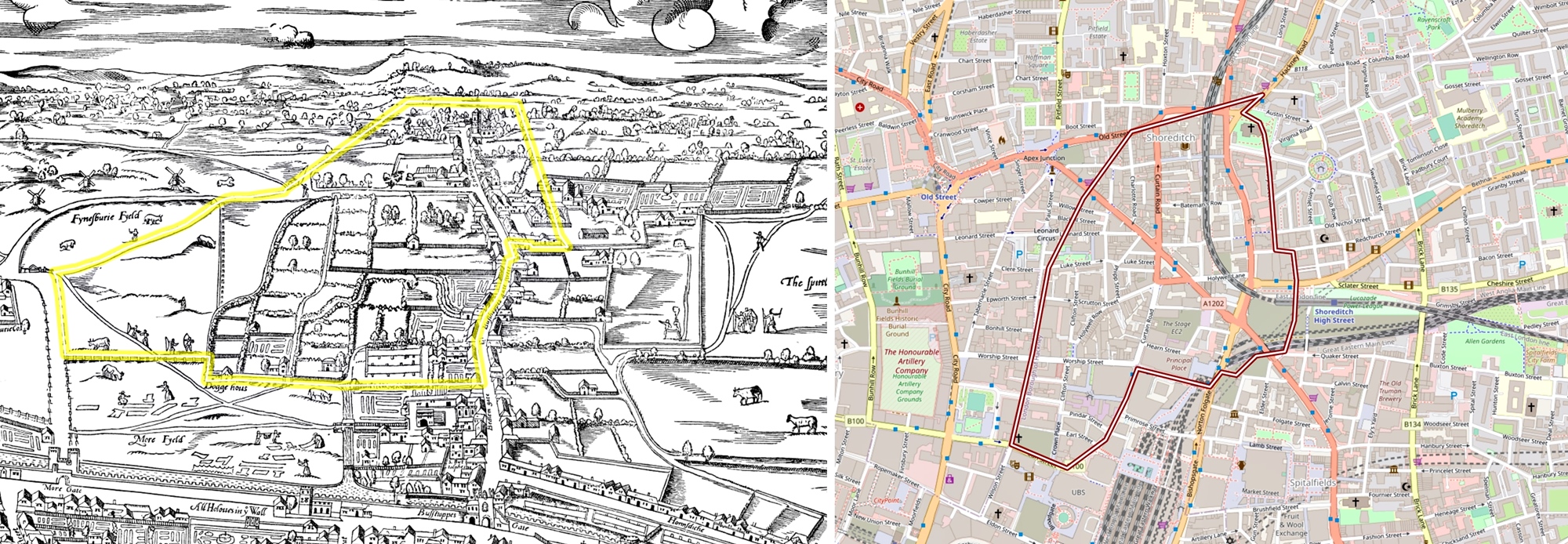

May 2022. In the warmth of late spring, Tudor Londoners headed into the surrounding villages. On Saturday 22 May 1568, John Willyamson went a mile out of the city to Shoreditch, with John Ryvers, Philip Pynchebeake, James Kenryicke and Ralph Boscocke. They were looking for birds’ nests, presumably to find some tasty eggs or chicks, but also to relax outside the rapidly growing metropolis. They may well have got hot climbing trees, because all five agreed to bathe in a pond in Bishopsfields. As the area was also used for brick and tile-making – there was already a Brick Lane nearby in 1485 – the pool may have been more complex and treacherous than the five friends assumed, and, while washing himself, John fell into ‘a depe hole’ in the pond and drowned.

April 2022. County coroners were not expected to investigate deaths on ships out of sight of land, but their reports on mishaps in harbours and estuaries provide intriguing snapshots of maritime life. John Awstine met his end at Bridport Mouth in Dorset, the harbour where the River Brit entered the sea, to the East of the present West Bay harbour. He was a sailor from Bothenhampton, the village between Bridport and the harbour. On 24 April 1582 he was on board the John of Bridport, a small ship of 20 tons, which was barely afloat in six feet of water. He climbed the mast with ‘a garland’, aiming to carry it up to the top. This may have been a garland of flowers – nineteenth-century ships raised them to celebrate a successful voyage – but was more likely a metal hoop or a ring of rope designed to strengthen the mast or prevent the rigging from rubbing on it. When he reached beyond the middle of the topmast, however, he paused. It was not clear to those watching whether he was tired out by bodily labour or taken by drink, but they repeatedly asked him to climb back down. Determined to reach the top, he turned around, but then he lost his grip and fell against either the tiller or the stays (‘repagula navis’) and into the sea, where he drowned.

March 2022. The clergy appear in accident reports in many different situations, not all of them to their credit. At 7 in the evening of Monday 6 March 1570, Thomas Jameson, rector of North Piddle in Worcestershire since at least 1561, was on his way home from Upton Snodsbury, two miles away. Unfortunately, he was ‘valde ebriosus’: very, very drunk. The road lay close to a stream called ‘Grafton broke’, one of a network running south to the Avon. At a place called ‘Myll medow slyppe’ he fell in and was drowned. Nor were his parishioners’ trials at an end, for his successor Richard Clough had to be deprived by the bishop in 1579 for unspecified offences. At least things were more settled after 1583, for the rector appointed then, John Jones, stayed in post until 1625.

Snaphance muzzle-loading pistol (c. 1600). The Royal Armouries, Leeds, Hunting Gallery, XII.1823. Click for a larger image and a detailed description.

February 2022. Firearms have always been hard to make entirely safe. Sixteenth-century designs improved on the use of a slow-burning match to ignite the gunpowder by developing locks such as the snaphance, in which a flint struck sparks to set the gun off. Such mechanisms were however liable to be set in motion accidentally. At Rainham in Kent on 8 February 1590, Jane Money was working as a maid in the household of a local miller. That afternoon she visited the house of a widowed relation of the miller, where another family member, Benedicta Batte, spinster, had left a snaphance handgun loaded on a table. Jane had with her a small dog and it jumped on the table, setting off the spring that drove the flint. Jane was struck in many places by the hailshot, shot of many small pellets used for hunting, with which the gun was loaded, and she died at once.

January 2022. Sixteenth-century winters were cold, and that meant firewood in the hearth and ice on the roads. The combination was fatal for nineteen-year-old Edmund Gellybrand of St Mary Cray in Kent on 15 January 1575. At 2 in the afternoon he was driving a cart, drawn by four horses and loaded with bundles of wood, down the road from the top of Blackheath Hill towards Greenwich. Without brakes, the best means he had to control the cart’s downward progress with its heavy load were the strength of the thill horse between the shafts and his own muscle-power and balance. All the way down the hill he supported the left side of the cart with his shoulder to slow it down. Suddenly, his feet slipped on ice and he fell. The left wheel ran over his jaw, crushing and breaking it, and he died at 2 in the morning.

December 2021. The holly and the ivy have long been favourite Christmas decorations, but ivy, clinging and tough but suddenly liable to snap, is not easy to collect. At 1 in the afternoon on 22 December 1560, at Horn Grove near Empingham in Rutland, Anne Atkinson, spinster, climbed an ash tree to get some. She had a ladder 8 feet long which she used to climb into the tree, and then drew up behind her in the hope of climbing higher. She pulled the ivy she could reach forcefully towards her, but it broke and she fell head-first from the tree. She hit her forehead on a stone, wounding it an inch or more deep, and when Elizabeth Haryson, wife of Richard Haryson of Horn, found her, she died within a quarter of an hour.

November 2021. Sometimes accidents recorded by coroners can be linked to evidence of very different sorts to enrich our understanding of local history. Jane Jordaine was washing her muslin clothes in a pond at Horner Wood in Somerset 10 am on 14 November 1593, ‘standynge uppon the brinke of the said poonde of water’, when a gust of wind caused her feet to slip. She fell into the pond and drowned, as so many other women did when either washing clothes or fetching water. But this was no ordinary pond. Jane was the wife of William Jordaine of Luccombe, ‘Iren man’, and the pond was ‘a certaine Iren mill poonde of water’.

We know from a Chancery case in 1606 that George Hensley of Selworthy and his brothers William and Robert had set up an iron mill at Luccombe ‘commonlie called Horner mill’ and in 1995-6 archaeological investigation found earthworks, buildings and waste material in Horner Wood suggestive of an iron working site. A substantial dam of stone and earth would have held back a pond – recorded in Jane’s inquest as 10 feet deep and 40 feet wide – to drive the hammer machinery housed in a stone building. Slag from smelting and smithing iron was found together with charcoal made from the oak, ash and birch wood that still grow in the area. Where the Chancery case illuminates the business history of the mill and the archaeological survey its practical operation, the sad fate of Jane Jordaine brings back to life the families who made it work.

October 2021. Internal trade in Tudor England is in some ways harder to reconstruct than international trade, but rivers were clearly of central importance. Flash locks enabled boats to pass mill-weirs, but their operation presented dangers, whether running boats fast downstream on the wave of water released by opening the lock, or dragging them upstream over the weir. Richard Webbe’s inquest was not held until more than four months after his death and far downstream from the site of his fatal accident, presumably after his body washed up from the river, but the account of his fate is vivid. He was a Reading bargeman. Between 9 and 11 on the morning of 30 October 1578, he was on the bank of the Thames near Wargrave in Berkshire. Together with other men he was ‘towinge or drawinge’ a boat called ‘a Westerne Barge’ through ‘Cotterells locke’, the lock by Shiplake Mills, with a rope tied to the boat. They must have been straining against the force of the river and the weight of the cargo. Suddenly, ‘hys feete slippinge or slydinge’, he fell into the river and was drowned.

September 2021. As guns spread through English society, people had to get used to the difficulties of storing and using gunpowder. It readily became damp and lost its explosive power, but drying it out was hazardous, as John Bennett learnt to his cost. On 6 September 1567 he was with others in ‘an armery’ at Godshill on the Isle of Wight. The Isle was kept in a higher state of military preparedness than most of the kingdom: French troops had landed there in 1545 and the 1590s would see a major programme of modernisation at Carisbrooke castle. John was holding a ‘corryer’, an up-to-date long-barrelled development of the earlier arquebus or handgun. He stood next to a chimney where there was ‘chafyngdysshe’ with burning coals. On the chafing or warming dish sat an earthenware dish holding ‘gonnpowder’ set to dry.

John inadvertently knocked over the dish and the powder fell onto the coals and caught fire. From there the fire leapt to 4 ounces of ‘cornepowder’, the grained powder used in handguns, lying covered, five feet away. When that too took light, it set off a ‘fyrkyn’, or small barrel, of corned powder. That explosion blew him against the doorpost as he tried to escape the armoury and crushed his head. Like two-thirds of victims in accidents involving guns or gunpowder, he died instantly.

Matchlock muzzle-loading arquebus (c. 1560). The Royal Armouries, Leeds, War Gallery, XII.8. Click for a larger image and a detailed description.

August 2021. Inquest verdicts were given by jurors, but what kind of men sat on juries? Combining inquest reports with other records can give us some idea of the qualifications thought suitable for a diverse selection of respectable adult men. Of the fourteen jurors who reported on the death of Henry Jones in an archery accident at Coventry in August 1526, for example, we can trace eight to varying degrees in the city’s overlapping tax, muster and food demand surveys of 1522-5. The most prosperous were Walter Taillour and William Andrewes, taxed on £5 or £6 and £4 worth of goods respectively, whereas three of their colleagues had no goods worth taxing. Four of them were fit for military service, whereas three, Taillour included, were too old, ill or weak to fight and only one, John Herres, was noted as having the equipment needed to serve as an archer. At least six were married and some headed full households: Andrewes and his wife had one child and employed two lads in his business and two servants, while Henry Mayet had an apprentice. They represented a range of the city’s textile and service industries. Andrewes was a baker, Mayet a shearman, and there were two tailors, while other Coventry juries featured the cappers who worked in its most famous trade.

July 2021. Lightning storms were a hazard of Tudor life when so many people worked in the open air. They killed victims from April to September, but July saw more deaths than any other month. In 1570, Agnes Daye, 12-year-old servant of Thomas Slege, was picking peascods in the fields at Hillington, Norfolk, when she was struck by lightning and killed instantly. In 1585, Jane Smythe, spinster, perhaps not much older, was walking towards the village of Walton near York through the ‘Intacke’ or field enclosed from the commons. Suddenly, as the jurors put it, great tempests, thunder and lightning flamed and came down from the sky. The strike set on fire ‘hir hatt and lynen clothing’ and the hair on her head and she too died at once.

June 2021. In the sixteenth century, as today, it was wise to carry refreshments on long summer journeys; wise, but risky. On 5 June 1572, Nicholas Jenckes and John Jackettes were taking two pieces of timber to the house of Henry Dorlynge at Bidford-on-Avon in the cart of their master, William Charlett of Cleeve Prior in Worcestershire. Jackettes was driving and Jenckes had a bottle clasped between his knees for safe keeping. At 9 in the morning they drove over the River Arrow, perhaps at Oversley, and stopped the cart, but as one wheel rested on a bank, higher than the other wheel, the cart collapsed. As it broke it fell on Jenckes, squashing the bottle into his genitals and wounding him so badly that he died three days later.

May 2021. Some jobs were clearly much more dangerous than others in the sixteenth century, but something could go wrong in more or less any occupation. Tailors were not much at risk, but George Broke was either careless or unlucky. On 25 May 1576, at Buntingford in Hertfordshire, he was working on some clothes brought to him by his neighbour. He picked up a doublet, doubtless resting it on his lap in the classic tailor’s cross-legged pose. He began to cut openings in the front of the doublet with a ‘Chesell’, presumably of the sort used to cut buttonholes. The chisel slipped – ‘dyd glyde’ – and pierced his right thigh. It must have been narrow, sharp and applied with pressure, for it gave him a wound only half an inch wide but four inches deep. He died at once.

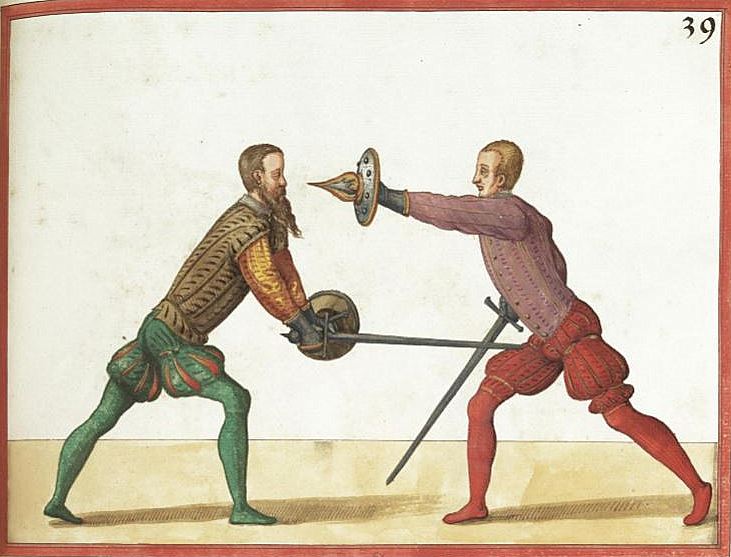

April 2021. Numerous fights ended in deaths classified as accidental. At times it is far from clear to us who was really in the wrong or why the inquest found for death by misadventure rather than manslaughter or murder. But in the case of John Weley the jurors wanted us to be in no doubt and did not spare us the details of his end. On Saturday 21 April 1543, they reported, at Shipston-on-Stour, then in Worcestershire, he drank so much that he could barely walk. He came to the house of George Browne, shouted abuse at him and tried to assault him with a staff. He then fell over backwards in the street. All the drink in his body came up through his mouth and nose and he died at once. Neither George nor anyone else, the jurors made clear, had touched him, and he clearly had only himself – or perhaps the drink – to blame.

March 2021. Sixteenth-century mills were dangerous not only because of their fearsome internal machinery, but also because of their unpredictable power sources. It was a day of tempestuous wind at Mucking in Essex on 18 March 1599 and Thomas Folly, miller, decided to take the sail-cloths off the sails of the wind mill. He climbed up one of the sails to pull on the rope that controlled the spread of the sail, but he had not, as the jurors pointed out, paid sufficient attention to his own safety. The critical mistake was his failure to secure the ‘gripe’ of the mill, which should have prevented the mill sails and the machinery connected to them from turning. The violent wind caught the sail, it turned and he fell to his death.

Detail from Kitchen scene with a maid and a boy by Floris van Schooten, c1615. Private collection. Click to enlarge.

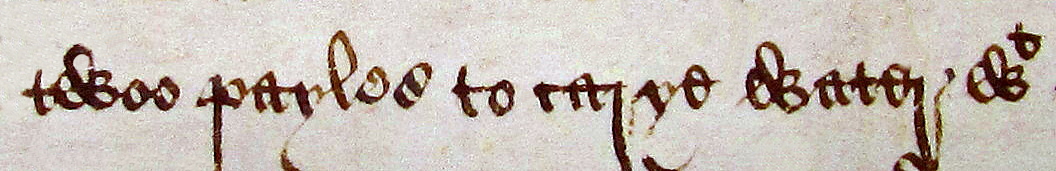

February 2021. Tudor households could be tense places. We might think first of troubled marriages, overbearing parents or abusive masters, but another source of friction was the relationship between teenage children of the house and their peers employed as servants. Occasionally, and tragically, we can eavesdrop on their spats. On 10 February 1545, at Pulborough in Sussex, Alice Bennett, aged 15, was in her master Thomas Onley’s kitchen. She was sitting on a stool, sewing, when Onley’s 13-year-old son John came in. John took the small spit used for roasting birds, heated the sharp end in the fire and burnt a hole in a post by the chimney. Alice ‘bade hym rest and leffe worcke, or ells she wolde tell his ffather therof’. ‘What, ffolle’, replied John, ‘what hast thou to doo therwith’? He put the spit back in the fire, intending to bore the hole deeper. She jumped up and ran to take it away from him. He span around, the spit stuck into her left thigh half an inch deep ‘and when she saw her owne blod, she ffell downe ded’.

January 2021. In an age before street lighting, long winter nights could be dangerously dark even in busy towns. At 8 in the evening on 31 January 1586, Matthew Wood’s servants were working on his boat, a ‘hoye’ or small sail-boat, at the wharf in Maidstone, Kent. Their colleague Elizabeth Dollynge came out of Matthew’s house with refreshments for them, a full ‘can pot’ of drink. She had a candle to light her way, but the wind blew out the flame and she stumbled into the Medway, where she was found drowned.

December 2020. Lockdown at home is frustrating, but Tudor imprisonment could be horrible. Confinement in ‘the Dungeon’ or ‘the pitt’ at Warwick gaol was made worse by the means of entry. On 26 December 1573, at 4 in the afternoon, Daniel Biddell, a tailor from the town, was being lowered into it by means of a rope on a windlass. He fell from the rope, hit the back of his head and died within an hour. The risk was persistent. Two and a half years later Griffin Jones fell in the same way and suffered the same injury when his hands slipped on the rope as John Coles, the gaoler and others were ‘lettyng’ him ‘downe’. But then dungeons were not meant to be pleasant. As the preacher William Pemble explained in 1629, God’s promise to Zechariah that he would rescue his people from the ‘Pit wherein is no water’ was such a mighty metaphor because the pit was ‘the worst place in the Prison, the Dungeon: a darkesome dirty Vault underground, whereinto Prisoners were let downe’.

November 2020. Wildfowl offered tasty meat in Tudor England but were hard to catch or shoot. One technique that came into its own as the days shortened in late autumn was batfowling. The aim was to catch unwary or roosting birds at the waterside. But there were risks. At Sonning in Berkshire on 21 November 1562, Thomas Gadge was out with others ‘batfowlyng’ at 11 at night at a lake in Burway Marsh. He saw a teal and threw his net over it, but overbalanced, fell in and drowned. On 27 November 1582 at Sawbridgeworth in Hertfordshire, again at 11 at night, John Shorte was in a ‘batfowlinge’ party when he met a more dramatic end. He was on the dark side of a hedge, trying to force out the birds, but as his companion Arthur Fayerfaxe beat the hedge with a staff he inadvertently hit John in the head and John died next day.

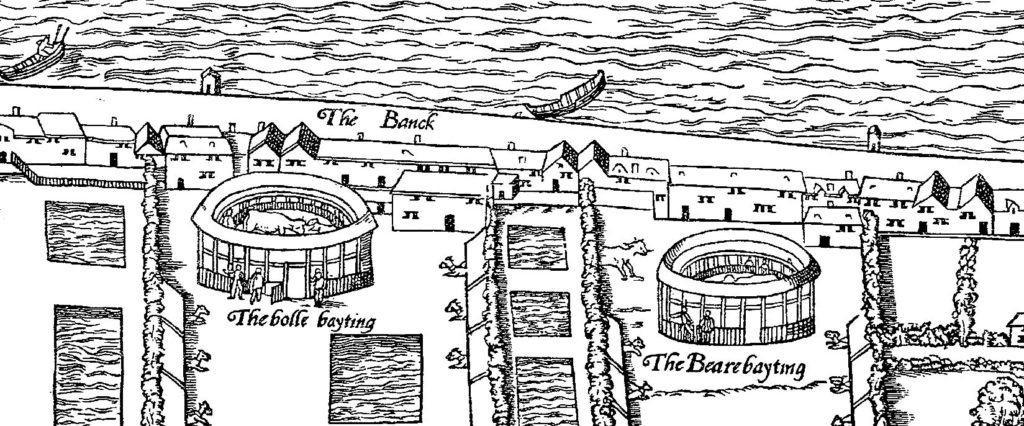

Tenter frames near fulling windmills to the west of Beverley Gate in Hull. Detail from John Speed, The theatre of the empire of Great Britaine: presenting an exact geography of the kingdomes of England, Scotland, Ireland,… (1603-1611). Cambridge University Library, Atlas.2.61.1, p. 65. Click to enlarge.

October 2020. Compared with most occupations in the sixteenth century, work in the rapidly growing textile industry was remarkably safe. Handloom weaving presented few of the risks that would be such a feature of the mechanised cloth mills of the industrial revolution. Yet occasional mishaps did occur. Leeds was a major centre for woollen cloth manufacture and there on 18 October 1565 George Waterhous met his end through one of the later stages of the cloth-making process. At 11 in the morning he was carrying ‘a tenter barre’, part of one of the tenter frames on which cloth was stretched out to dry, from the house of Augustine Wilkynson, gentleman clothier, to ‘the Tenter grene’, where there was room to set the frames up. He stumbled, the bar fell on his head, and he died at 4 am next day.

September 2020. The watermen of London and its surrounding villages were, as has often been remarked, the taxi drivers of their day. They ferried passengers not only between London and Southwark, as an alternative to the single crowded bridge, but also to other key sites along the Thames. Working small boats on a busy river, their trade had many dangers. In September 1579 alone, two Lambeth watermen met their ends in different ways. On the 13th, between 7 and 8 in the evening, Roland Stephenson drowned in what was in effect a parking accident. His colleague William Towseye dropped him off from one boat into another which was tied to two more. The aim was to reach a fourth boat and take it from Stangate, where they were all moored, round to Lambeth bridge, but Roland had neither the right oars nor, the jurors thought, sufficient strength to perform the necessary manoeuvre and he fell into the Thames. Five days earlier, William Harforde had come to grief in more predictable fashion. He was crossing from Westminster bridge to Stangate in Lambeth between 3 and 4 in the afternoon, sitting on the outer edge of the highest part of the boat. He fell backwards off the boat to his death, but then he was, as the jurors pointed out, oppressed by ale or ‘drounck’.

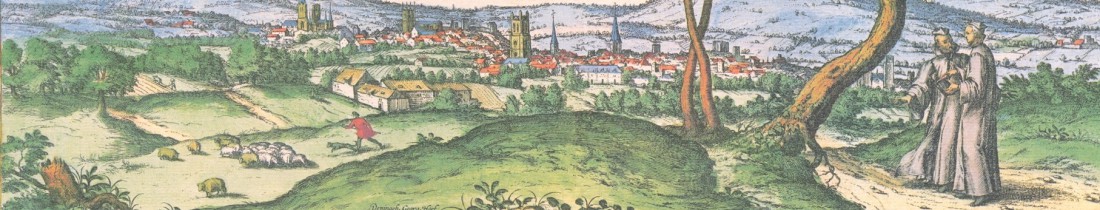

Boats on the Thames. Detail from the 1574 map of London. Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg, Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Cologne 1574). Folger Shakespeare Library, MAP L85c no 27. Click to enlarge.

August 2020. The Welsh were widely spread in Tudor England and especially in the border counties. Many settled, but others travelled for work. At Little Ness in Shropshire three met tragedy in 1580. Cadwalader ap Hugh ap Dafydd, Thomas ap Hugh ap Dafydd and Ieuan ap John ap Hywel ap Jencyn were labourers from ‘Llangonna’ in Montgomeryshire, perhaps Llangyniew, 23 miles away. On the night of 23 August, they were asleep in a bed in a barn on the farm of Richard Kynaston, gentleman, near a stack of wheat. At 11 p.m. the stack partly collapsed. They were suffocated as 96 sheaves fell on top of them.

July 2020. As our May 2013 accident showed, maypoles were a surprisingly dangerous feature of the Tudor springtime landscape. But the fun, and the risk, did not stop with the spring, as summer-poles decorated with flowers were the focus of revels to midsummer and beyond. At Reading on 19 July 1542, John Cressewell overturned his cart and broke his back when he ran over a summer-pole fixed in the ground. Perhaps it was like the ‘summer polle of byrche’, 40 feet long, standing in the roadway at Westbury in Shropshire in 1565. It fell in the wind at 6 in the evening on 28 June 1565, hitting Alice Chilton as she crossed the road with little Elizabeth Chilton in her arms. Elizabeth, struck on the head, died at once, but Alice lingered, doubtless in mourning and in pain, until 11 the following morning.

Detail from an initial in Le Livre des hystories du Mirouer du monde (c. 1480). Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Français 328.

June 2020. The strawberry season has always been exciting for adults and children alike. In summer 1539 it proved too exciting for three-year-old Richard Sharp, son of Thomas Sharp of Stone near Dartford in Kent. At 4 in the afternoon on 14 June, he was picking strawberries at Bean in the south of the parish. They grew between a pond called ‘lynsale’ and a road called ‘a pakwaye’, presumably used by packhorses, running, at right angles to Watling Street, from Bean to Green Street. Perhaps stretching out for a juicy berry, he fell into the pond and drowned. There he was found by two local youngsters, fourteen-year-old John Rychemond and thirteen-year-old Alice Johnson.

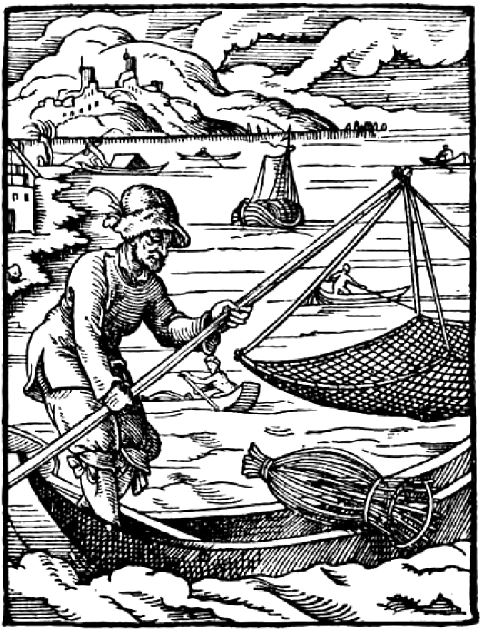

May 2020. Fishing accidents were common in the sixteenth century. Fish, rather than meat, was supposed to be eaten on many days of the year even after the Reformation. It might be caught to cook or sell in many accessible rivers, streams and ponds inland, as well as along the coasts. However, accident reports rarely specify just what fishermen were aiming to catch. Hugh Jones, who drowned on 20 May 1530 at North Hinksey, on the Thames just west of Oxford, is an exception. He was catching ‘Craves’ or white-clawed crayfish, the tasty small crustaceans now almost eliminated from the Thames by their larger cousins the American signal crayfish, when he fell into a ‘myre’ from which he could not get out.

Hedgelaying. Window detail, St Mary and All Saints church, Checkley, Staffordshire. Click to enlarge.

April 2020. Hedges and fences were controversial in Tudor England, targets for enclosure rioters when they blocked access to common land. But they could also be dangerous to build or mend and spring was a prime time for such mishaps. On 8 April 1583, at Heybridge in Essex, John Parbye was mending the hedge or fence between the common marsh called the ‘borough marshe’ and the inner marsh called the ‘ynmarshe’. He was sixty years old and weak from an illness. As he tried to drive a stake into the slippery ground, he lost his footing, fell into a ‘creke’ and drowned. Even those not working on the hedge were at risk. On 15 April 1567, at 3 in the afternoon, Thomas Wraye of Timberland, labourer, was walking through the fields of Branston towards Lincoln. He came too close to a cart piled high with ‘tynsell’, brushwood for hedging or fencing. A gust of wind blew the cart and its load over and Thomas was crushed.

March 2020. Bridges presented dangers for those crossing them, but also for those passing beneath. The stone piers or wooden piles on which larger bridges rested created tricky currents in the water and made dangerous obstacles for boats. John Colye of Lambeth, waterman, came to grief on the Thames at Windsor on 3 March 1581, between 6 and 7 in the morning. He was rowing in his own boat near a bridge called ‘the towne bridge’, the wooden predecessor to the current stone bridge. The boat was suddenly caught by the violent course of the water, carried into ‘the pyles’ of the bridge and crushed against them. As the boat sank, he was dragged away from it by the current and drowned. Similar problems with bridges sank boats on the Wye at Hereford in 1533, on the Trent at Swarkestone in 1541 and on the Thames at Southwark in 1580.

February 2020. Tudor towns were full of animals and they needed water to drink. The easiest source was usually the local river, but that could mean taking horses or cattle to watering places whatever the weather. Elizabeth Tempyll was servant to a York shoemaker, James Tesymond. Between 4 and 5 on the afternoon of 7 February 1541 she took the household’s black cow with a white face to St Leonard’s Landing on the Ouse, where Lendal Bridge now stands, to drink water. The river was frozen and the cow fell through the ice into water several feet deep. Elizabeth and three other young women, Agnes Clay, Agnes Dunwyche and Elizabeth Greynacres, tried to pull her out with a rope tied to her horns, but the ice broke again and all four women drowned. Perhaps they should have gone to York’s recognised ‘watteringe place’, near the Queen’s Staith. Then again, that did not help Francis Mawson when he rode a grey mare into the river there in March 1589. The mare stumbled on a log in the water and fell and both horse and rider drowned.

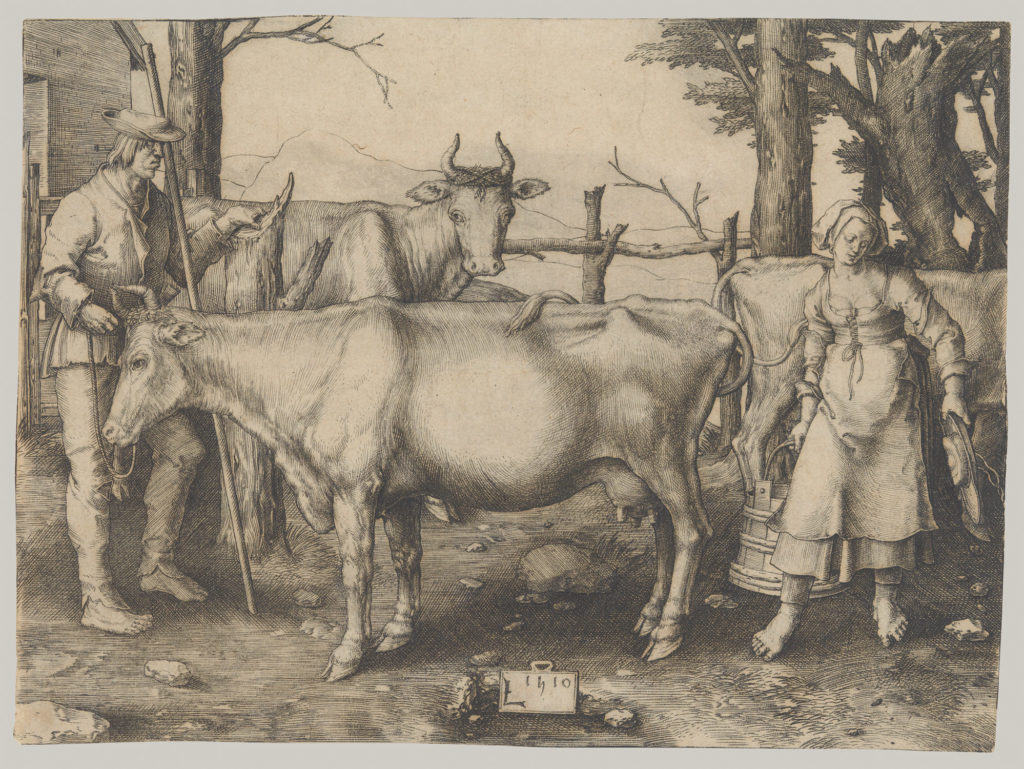

The Milkmaid. An engraving by Lucas van Leyden (1510), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, 41.1.24. Click to enlarge.

January 2020. Tudor legislators might be slow to respond to the dangers posed by accidents, but they were not fatalistic in their attitude to risk. On 30 January 1581, an inquest at Much Birch in Herefordshire investigated a recent disaster. On 1 December 1580, John Swannycke and James Meirick were at either end of the barge that served as a ferryboat at Wilton, steering it across the River Wye. A sudden gust of wind frightened a horse and its trampling drove Swannycke from his post. Without steering, the boat turned in the wind and sank. Swannycke and sixteen passengers drowned. The passengers, labourers, husbandmen, weavers, spinsters, housewives and a tailor, mostly came from the western side of the Wye – Aconbury, Bridstow, Goodrich, Hentland, Llangarron, Pencoyd, Sellack and Much and Little Dewchurch – but also included a shoemaker from Much Marcle to the East.

Wilton Bridge.

Eighteen years later an act of parliament, reacting to such perils by providing for local taxation to fund a bridge to replace the Wilton ferry, made its way through the Commons. At first reading on 12 December 1597, Sir Thomas Coningsby, a combative MP for the county, opposed it on the grounds that there were too many taxes already, that Herefordshire was too poor to pay them, and that there were so many bridges on the county’s rapid rivers that the cost of maintaining them all would be prohibitive. But a committee was established to work on the bill, led by Sir John Scudamore, the other knight of the shire for Herefordshire. It included members from the wider region, such as William Oldsworth of Gloucester and David Williams of Brecon Boroughs, experienced legislators such as Sir Robert Wroth, and Herbert Croft, a scion of the family most opposed to Coningsby in local politics.

The final version of the bill, enacted into statute in February 1598, pulled out all the stops in justifying its provisions, as Tudor acts tended to do. The ferry carried trade to Ross-on-Wye and beyond from Herefordshire, Monmouthshire, Brecon and most of South Wales, but the river it crossed was ‘very furious and dangerous, and with a small Rayne doth suddenly swell and ryse uppe’. The ferryboat had often sunk, so that thirty or forty people had ‘not longe since’ been drowned, while others had had to swim for their lives, or had had their arms and legs broken, or had been trampled by other passengers or by horses and cattle sharing the boat. A bridge would solve the problem and so it should be built within seven years at the costs of the county’s inhabitants, bolstered by any voluntary contributions that could be gathered in Wales. Tolls were to be levied – 2d for a cart, 1d for a packhorse, 3d for twenty sheep, 6d for twenty cattle and so on – to pay for the bridge’s upkeep and compensate Charles Bridges esquire, lord of the manor of Wilton, who currently benefited from leasing out the ferry, to the tune of £10 a year. All was to be done under the supervision of the county’s Justices of the Peace, Scudamore, Croft and the cantankerous Coningsby among them. The bridge, built in sandstone, survives to this day.

December 2019. The procedure for investigating sudden death could be presented with a challenge by accidents with multiple victims. If the dead were found at different times in different places, then separate inquests had to be held over each corpse. Yet coroners and the communities they served seem to have responded flexibly and with good sense to maximise local knowledge and administrative continuity. On 22 December 1582, a ferry-boat sank at Gunthorpe Ferry on the River Trent in Nottinghamshire, overturned by the restless horses taken aboard. In the boat were Nicholas Northe, a labourer from East Bridgford, just south of the ferry crossing, Germaine Curzon, a gentleman from nearby Shelford, and Francis Randle, another labourer. All three drowned, as did one of the horses, while the other two horses presumably swam to safety. Their bodies were eventually recovered down-river, Randle and Northe at Kneeton on the right bank and Curzon at Hoveringham on the left bank, but at sufficiently different times that the inquests took place four months apart. None the less, the juries assembled were well designed to reach informed and consistent verdicts. Robert Peper, who found both the bodies at Kneeton, served on the two juries that sat there, three other men sat on two of the juries, while Ralph Wilkynson and John Harropp of Hoveringham served on all three.

November 2019. Modern accident statistics are always capable of surprising us with the damage that can be done by apparently innocuous household objects, from flowerpots to underwear. Things were the same in the sixteenth century. Helen Ricardes of Wotton-under-Edge in Gloucestershire was a married woman, the wife of Philip Ricardes, but on 10 November 1501 she was at the rectory in Wotton, perhaps working as a servant or cook. At 10 pm she walked downstairs, carrying a candlestick, and fell. The candlestick struck her in the right side of the body and she died at once. The report is not as detailed as many later in the century, so the precise role of the candlestick in her death is not quite clear, but the jurors clearly thought that it was decisive enough to place it at the centre of their explanation of poor Helen’s demise.

October 2019. Rivers in flood have a terrible power and one that most sixteenth-century houses were too flimsy to resist. At Kendal on 7 October 1567, the River Kent rose and washed Nicholas Yanson’s two sons out of his house in their bed, drowning one of them. The destruction wrought on Margaret Atkensone’s home on 5 January 1565 was even more drastic. The widow was in her house, near the river in Croft-on-Tees, when the torrent submerged it at 4 in the morning and the building collapsed, one beam falling on her head.

September 2019. Wells were better dug deep to provide a clean and dependable water supply. But depth could make it dangerous to mend, clean or investigate them, not only because of access difficulties, but also through lack of breathable air. On 15 September 1540, at Brimington in Derbyshire, Jane Myller set out at 3 in the afternoon to check whether water ‘dyd spryng’ in a well. She climbed down it using a rope, but was overcome by what the jurors identified as the same problem afflicting miners working at depth, ‘a certayn dampe’ called ‘the colpytte dampe’. She was not the only victim. Arnold Hall, repairing a well at Alcester in Warwickshire, William Marche, retrieving a well bucket at Stainswick in Berkshire, and Thomas Tyndell, draining and cleaning the well of Christopher Harbert, merchant, at his house on Pavement at York, all suffocated in the same way. The scales involved are shown by the report that the well John Humfery was repairing when he succumbed at Codford St Peter in Wiltshire in September 1549 was 60 feet deep.

Sometimes more than one life was lost. At Wednesbury in Staffordshire in September 1539, Richard Chesshyre and Thomas Harwodde were building a well for Nicholas Hopkyns. Richard was felled by what the jurors this time called an odour of the ground named ‘yerthe damp’, Thomas rushed down to help him and both died. At Micheldever in Hampshire in July 1543, Robert Longe went down a well to rescue a piglet, but when he get into trouble Christopher Thirkyld climbed down to get him out. When he too failed to return, John Frere went to look for them both and he perished with them.

The harvest in August. Detail from Simon Bening’s illumination in the ‘Golf Book of Hours’ (c. 1530), The British Library, Add MS 24098, fol. 25v. Click to enlarge.

August 2019. Harvest could be a dangerous time not only for those working in the fields to gather the crops, but also for those supporting them. At Chellington in Bedfordshire on 31 August 1529, Jane Wright, 15-year-old servant of John Dale, was walking through a field called ‘parke feld’ with two pots of drink for her master’s harvesters. Another of his servants, John Hynde, whipped the four horses driving a cart across the field too hard. The horses came up fast behind her on a green headland and when she tripped and fell the cart ran over her head.

July 2019. Intestinal worms were an unpleasantly common affliction in sixteenth-century England. In his book on horsemanship in 1566 Thomas Blundeville explained that one of the three kinds of worms affecting horses was ‘long and rounde, even lyke to those that children do most commonly voyde’. In June 1580 at Lawshall in Suffolk fourteen-year-old Anne Wyffyn resolved on drastic action to cure herself. She ground up some ratsbane – arsenic used as rat poison – into a very fine powder, mixed it into a pot of ale and drank it, aiming to kill the worms and not suspecting that she would poison herself in the process. She soon fell ill, however, and two days later she was dead.

Ore extraction. Detail from the altar (1521) in St. Anne’s Church in Annaberg-Bucholtz, Saxony.

Panfield Hall with remnants of the moat.

January 2019. We tend to think of hermits as a feature of the heroic age of medieval religion rather than the early sixteenth century. But hermitages dotted the early Tudor landscape, often linked to chapels, monasteries or castles, and some still felt the spiritual call to inhabit them. John Hastyngs was the hermit at the chapel of St Anne in Boxley, Kent. He was aged and weak of body and at 9 in the evening on 7 January 1512, walking back to his house by the chapel on a particularly dark night, he fell into a ditch by the roadside and drowned.

December 2018. Criminal clerics and the system of benefit of clergy, by which they evaded some of the normal processes and penalties of the law, were hot topics in medieval and early Tudor England. We do not know the charge against Thomas Sadd, priest, but we do know that on Tuesday 28 November 1525 he was, for certain reasons as the inquest jurors put it, in the custody of Thomas Banys, deputy doorkeeper at Ramsey Abbey in Huntingdonshire. Attempting a night-time escape, he managed to break out of the place in which he was being held, but fell from a height and incurred an injury to his right leg which led to his death six days later, on 4 December.

Ramsey Abbey gatehouse.

November 2018. Attitudes to accidents can be hard to recover from the matter-of-fact reporting of the coroner’s inquests. But occasionally the jurors offered revealing explanations for the fatal outcome of some otherwise less than catastrophic injuries. In two cases these involved the astrological medicine widely disseminated in sixteenth-century society through cheap printed almanacs. On 6 November 1580 at Bow Brickhill in Buckinghamshire, Bridget Chyvell fell and wounded herself on the inside of her left thigh with a knife. She died instantly, the jurors opined, because in that ‘leg and place the sign will rule at that time’, presumably a reference to the astrological conjunction. Similar ideas shaped the account of how Simon Reve, a tanner of Beccles in Suffolk, met his end in December 1544. He was passing through the courtyard of James Canne’s house followed by his two mastiff dogs, one red and one white. His dogs quarrelled with Canne’s greyhound, eventually biting it to death, but as he tried to break up the fight he kicked the white mastiff and wounded the instep of his right foot on its ‘toyshe’ or canine tooth. Though his wound was only one-eighth of an inch deep, he died from it nine days later because, the jurors explained, the sign of the foot was then reigning in that place.

October 2018. Most of those who died in Tudor accidents expired either immediately from catastrophic injuries, hours later from the effects of major burns or blood loss, or a week or ten days later, presumably from blood poisoning, blood clots or similar problems. Occasionally, however, juries were confident in attributing death to an event many months before the victim’s demise. This was the case with William Burre, a labourer of Margaretting in Essex. He died on 2 October 1589 and the inquest on his body was held the following day. What it found was that he had been on his deathbed since 12 November the previous year. He had been holding up the front end of a cart belonging to John Tanfyld of Margaretting, gentleman, while others mended it. The cart moved, he fell over and a substantial piece of timber fell on him. His back had been, as the jurors put it, gravely crushed, and he never recovered.

September 2018. Almost all those who died in sixteenth-century accidents were too humble in station to leave any permanent memorial behind them. One early exception was Walter Elmes, the rector of Harpsden in Oxfordshire from 1508 to 1511 and a member of the family who were lords of Bolney manor and patrons of the church. On Friday 15 July 1511, presumably a hot day, he took off his clothes and went into the Thames. He drowned in deep water and his body was found at Wargrave on the Berkshire side of the river. He was buried at Harpsden, where his brass shows him in his vestments but gives his date of death as 5 August, between the date for the drowning given in the inquest and the date the inquest was held, 18 September.

August 2018. The wise drinker knows when to stop. Thomas Beettes, a butcher, went out on 5 August 1589 for a few ales with Benjamin Colthurst, George Greathead and others at the alehouse of William Shorloke in Shenfield, near his home in Brentwood, Essex. They drank and jested with William for an hour or more, at which point Thomas realised that he was nearly drunk and decided he had better walk home alone to Brentwood. He was wearing on his feet ‘a payer of slyppers’, which may have been good for relaxing in, but perhaps not for an unsteady walk. The lane ran by a ditch and when he stumbled and fell in face-first, so the jurors delicately concluded, he must have been so dispirited by the force of the fall and the intoxicating effect of the drink that he could not help himself get out and so drowned by misfortune.

July 2018. Looking for things put away in the loft can still be a hazardous occupation in some houses, especially as we age. For John Rowe, a sixty-year-old tailor of Milverton, Somerset, it proved fatal. At 10 in the morning on 2 August 1589 he went up into a little room in his house to search for a key which he had lost. While there he sat down on a wooden panel which lay across the beams or joists of the room. The joists had not yet been covered with boards, so when he slipped backwards off the panel he fell through them and down to the ground, landing on his shoulders and head, knocking out ‘his breth’ as the jurors put it, and dying on the spot.

June 2018. Difficulties with mobility afflicted the elderly, disabled or injured at all social levels in sixteenth-century society as they do today. Crutches were an aid to those who found trouble in walking, but could not always prevent mishaps. Robert Tappyn of Swineshead in Huntingdonshire was a tailor described as ‘lame’, ‘impotent’ and ‘decrepit’. On 20 May 1583 he was trying to cross a plank bridge over the River Nene in the fields of Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire, but the wooden ‘crutche’ which he used to hold up his body, judged to be worth a halfpenny, slipped and he fell into the river. Years earlier and miles away a very similar accident led to the death of Nicholas Ellerkar of Tholthorpe, Yorkshire, gentleman. Before dawn on 6 November 1516 he was walking on his ‘crouches of wodd’ from Tholthorpe to a place called ‘Ravensike bank’, but he fell into the River Swale and drowned.

May 2018. The fifteenth-century fan vault of Sherborne Abbey church in Dorset is still much admired today. On Saturday 17 May 1589, the day before Whit Sunday, Robert Michell’s wonderment at its intricacies sadly cost him his life. He had been ringing the bells with other parishioners and afterwards, between noon and 1 p.m., stood in ‘the belfrey’ looking up at ‘the vaulte’. A stone of great weight fell from the vault and hit him on the left side of the head, killing him instantly. His body was laid out in the church when the jurors came to view it and give their verdict on his end; as sophisticated Elizabethan townsfolk, four of them were able to sign their names to the coroner’s final report.

The fan-vaulted ceiling of Sherborne Abbey.

April 2018. Sports such as wrestling, football and throwing the hammer presented obvious dangers to those who played them in the sixteenth century, but tennis was surely safer. Not so for Thomas Wright, a household servant from Milton in Dorset, who was playing tennis, probably a version where the ball was struck with the hand rather than with a racket, in a pasture at Milton at 11 in the morning on Friday 7 April 1581. His ball landed on top of a wall and he climbed up to retrieve it, but fell backwards into a brewing cauldron full of boiling wort. Badly scalded, he died at 11 that night and the wort, forfeit to the queen as the cause of his death, was distributed to the poor people of the village.

March 2018. Water causes problems for most extractive industries. At Quethiock in Cornwall, a centre of slate mining for hundreds of years, sixteenth-century miners found a practical but not entirely safe way to deal with the flooding of their pits. At 8 in the morning of 28 March 1581, John Graye was standing on a ‘flacke’, a wattled hurdle, which had been lowered with four ropes into a deep pit from which ‘healing stone’, slate for ‘heeling’ or roofing houses, was dug. From the hurdle he was reaching into the pit and working hard to throw out the water, but one of the four ropes broke and he was tipped into the water, where he drowned.

A young girl learning to write. Detail from Signboard for a Schoolmaster by Ambrosius Holbein (1516), Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel.

February 2018. Sixteenth-century people could on occasion show great consideration to animals. On 15 February 1586 a dog fell down the vicarage well at Lynsted in Kent and the vicar’s wife organised a rescue mission. At her request and of his own free will the vicar’s servant William Fyssher tied himself to the great rope and chain of the well by a belt, climbed into the well bucket, and was let down into the well by other honest and trustworthy inhabitants of the village. Unfortunately the contraption was not built to take his weight. The small rope connecting the chain to the great rope broke and he, the bucket and the chain fell into the water at the bottom of the well, where he drowned, presumably leaving the dog to its fate.